Village architecture in the high Dauphiné

This post is based on a talk I prepared for my recent International Mountain Leader summer assessment in Samöens. Candidates have to deliver two ten minute talks on topics related to the Alpine environment. I chose to use village architecture as a framework to talk about the geology of the region near Les Deux Alpes. The stone used for building reflects what can be found in, or on, the ground nearby, so the architecture here is closely related to the geology.

Introduction

People have always used the resources available from their environment to build with. In the Alpine valleys around the Ecrins massif, trees are not as abundant as elsewhere in the Alps. Here, stone replaces wood as the traditional building material and the geology of the region is reflected in the different rock types used.

The Ecrins massif was originally named the Massif de Pelvoux. In 1836, Captain Durant made the first ascent of Mont Pelvoux only to discover the yet-to-be-named Barre des Ecrins towering 100m higher.

Oisans Slate

During the Mesozoic Era (65-245 million years ago), the Tethys sea covered the Oisans region. Layers of sedimentary limestones and clays were formed on the bed of this sea. As the Eurasian and African tectonic plates collided at the start of the Cenozoic Era (65 million years ago to present day), these layers were compressed and folded and the clay layers metamorphosed into slate. The results of the folding can be clearly seen in the folded rock faces around Bourg d’Oisans.

Almost every village in the Oisans had its own slate quarry or mine. The slate from Venosc was the best known and was used across France. In the Dauphiné region, slate roofs are much more common than the wooden shakes seen across the Alps.

Laffrey Limestone

Towards Grenoble, the terrain around Laffrey was shaped by extension faults in the Mesozoic. Horsts and graben formed shallow and deep regions beneath the Thetys sea. Sediment deposited in the deeper areas formed thick clays, while in the shallow areas limestone was formed.

The compact Laffrey limestone tends to have strata tens of centimetres thick, ideal for building blocks. It is used extensively in Laffrey and Vizille, whilst limestone buildings are rare in the heart of the Ecrins.

Travertine and Calcareous Tuff

Travertine and tuff are formed when dissolved limestone is deposited by springwater. This happens when water flows underground through limestone, dissolving traces of the rock on the way. Tuff has a higher vegetable content than travertine. In the Ecrins, sources of tuff are found in numerous sites e.g. the ‘petrified waterfalls’ around the Plateau d’Emparis. Travertine is produced in the hot springs of Monetier les Bains. The latter rock may be more familiar to many as the material that stalactites are made from.

Both rocks are soft and easy to work – they can be cut with a handsaw. Church steeples built from tuff are a common sight across the Ecrins, while travertine is used in the vaulted ceilings of local farmhouses.

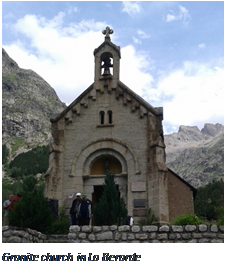

Granite in the heart of the Ecrins

The base layer of the region consists of igneous granite, formed 300 million years ago and covered by layers of sedimentary and metamorphic rocks deposited afterwards. Much later, with the tectonic plate collision creating the Alpes around 65 million years ago, the granite was lifted upwards. Subsequent erosion left the granite exposed again.

In the remote villages of the Ecrins, granite was often the most readily available building material, as evidenced by the number of granite dwellings and other buildings to be seen.